Talk given at University of Cumbria, Ambleside as part of the Cultural Landscapes talk series run by Penny Bradshaw, in October 2025.

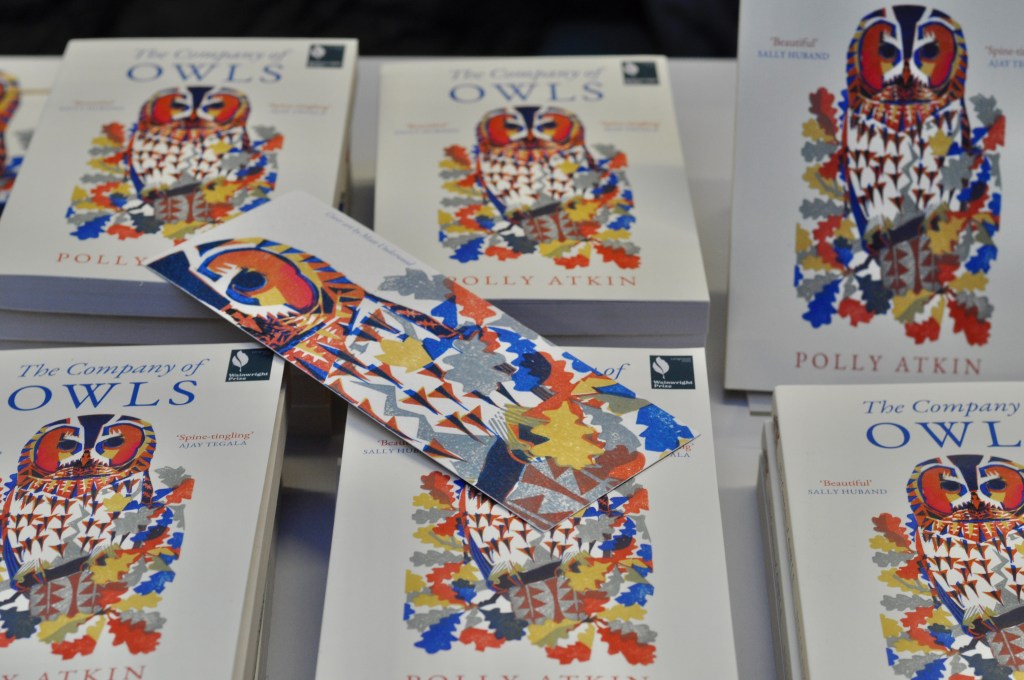

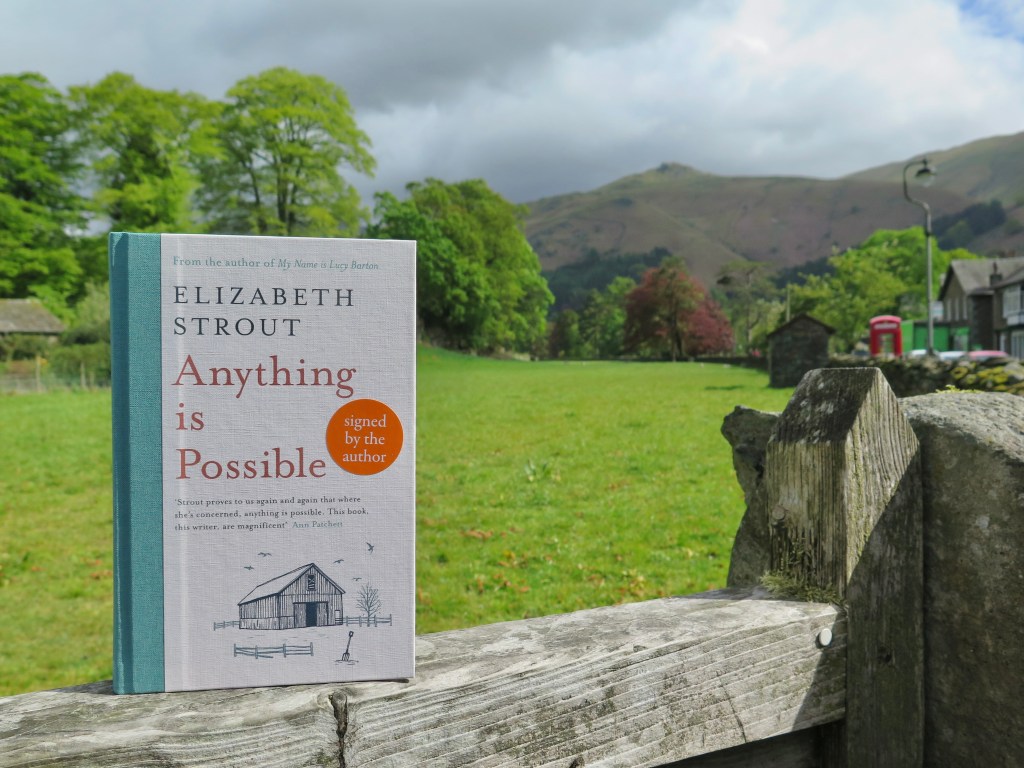

Some time in the mid twenty-teens, when twitter was still twitter, and still a place to make connections and jokes, my partner Will stepped out of the bookshop where he had been working part-time for years, carried a book across the road, and positioned it on a gate.

For a couple of years he had been sharing photos of books from the Sam Read Bookseller twitter feed as it grew, but a combination of poor lighting inside the shop, and the increased interest he got on posts which included the lake district landscape had been driving him to try to take more pictures of books outside the shop. He’d started by just standing outside the door and holding a book up against the backdrop of the fells, which worked okay, but didn’t always show the books off to best effect.

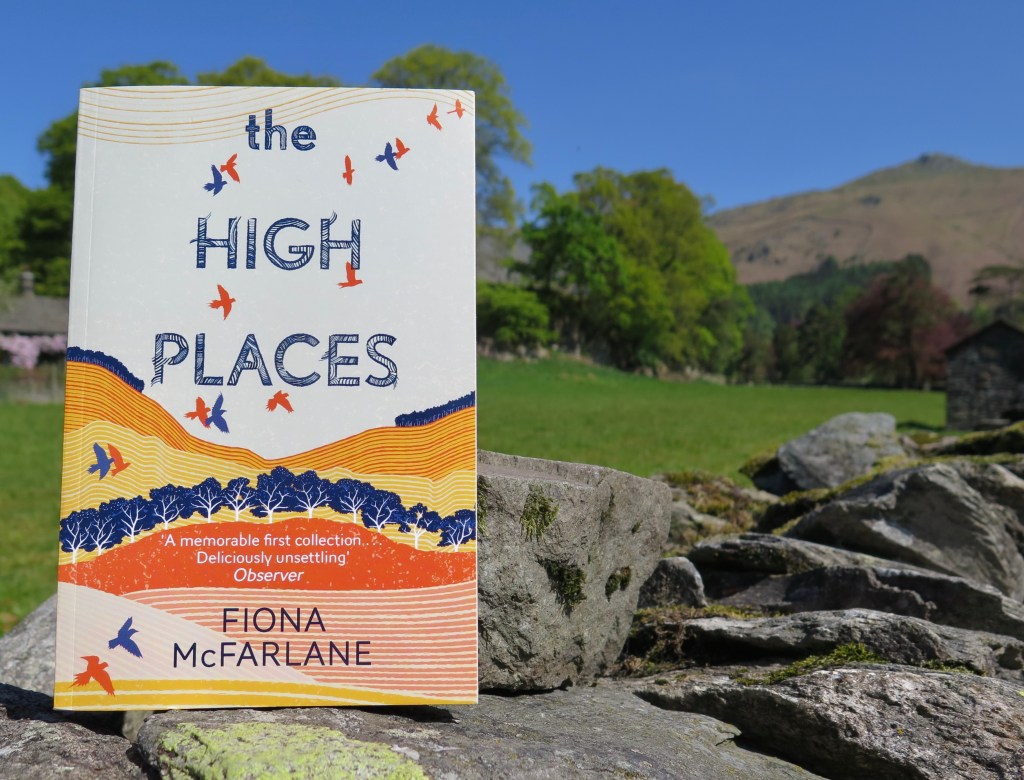

Next he tried nipping across the road and balancing books on the drystone wall opposite.

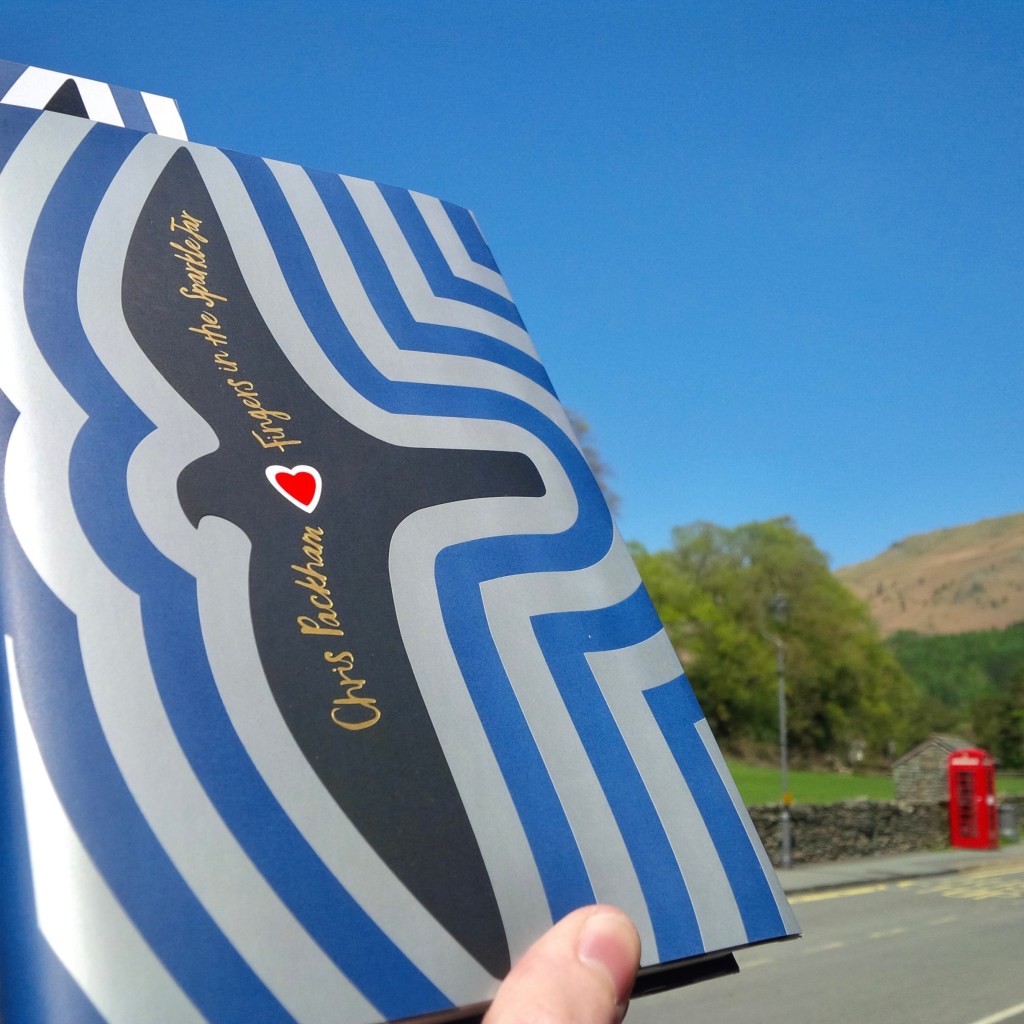

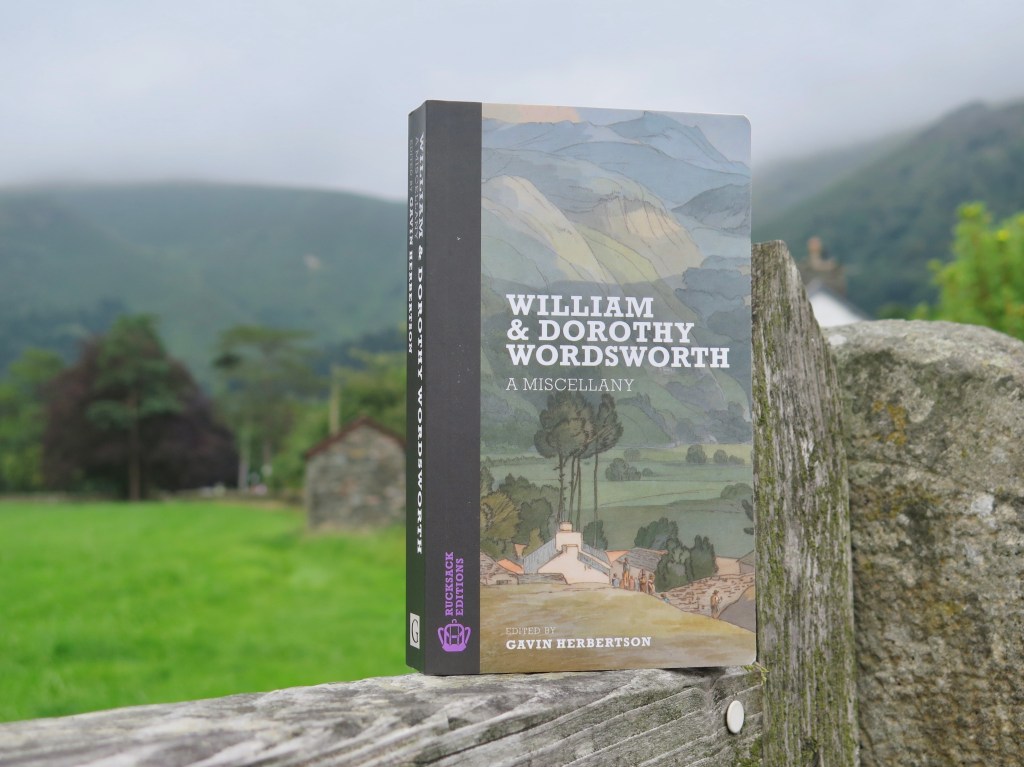

Through trial and error he realised that balancing a book upright on the field gate gave the best light and framing. By the end of the autumn of 2017 it had already become a standard image for the shop social media – a book or stack of books on the gate opposite. People seemed to love this combination of book recommendations and the landscape of the lakes.

It was a quick and easy way for Will to share interesting books without having to think of anything clever to say about them during a busy day, as the landscape seemed to say enough by itself. The gate became the book gate, and visiting writers would have their photo taken by it too.

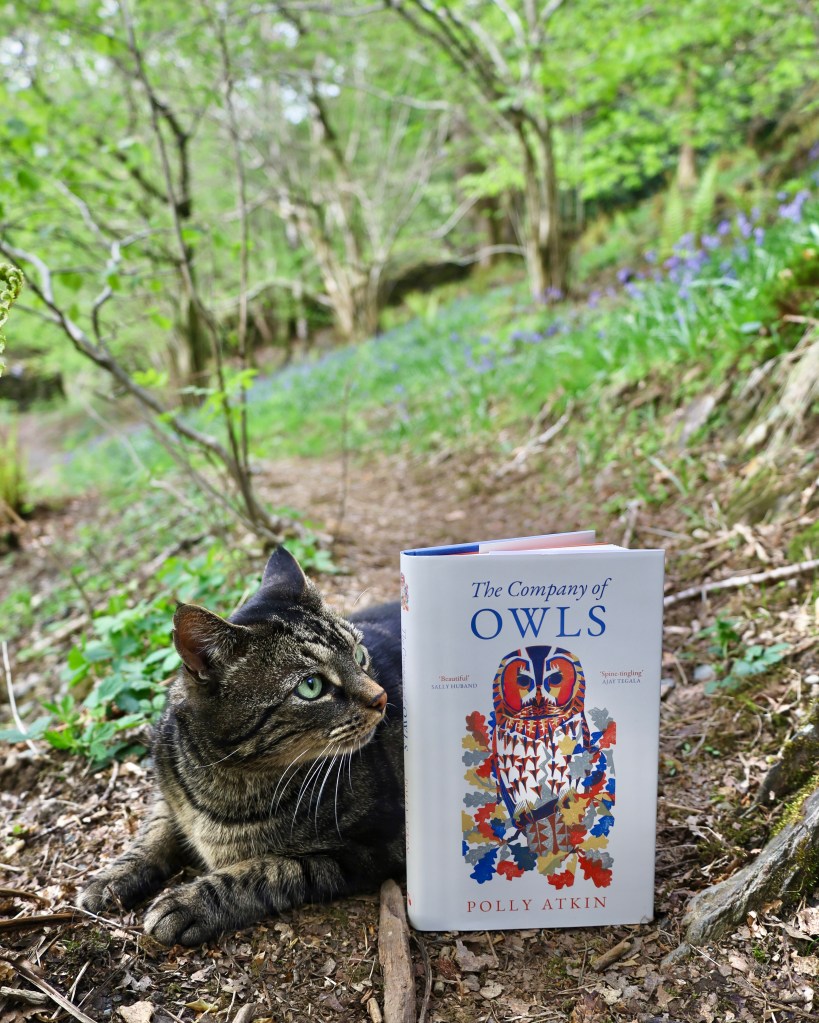

Outside shop hours we found ourselves taking photos of books in other favourites spots we found made good book backgrounds: a little crag looking down over Rydal Water, particular stones on particular walls, the lake shore. If the light in the shop is bad, our house is black hole, so it made sense if we wanted to share excitement about a book to take it out for a wander. It became a thing. I took photos of Will taking photos of books, lying or crouching to get the best angles, propping books up with jumpers or rocks because he never remembered to bring any props.

When my books which included swimming were published I wanted to photograph them by the lake that played such a large part in them. I’ve learnt a lot through that process. Through a lot of trial and error I eventually found which rocks allowed you to stand a book on them and get a good reflection too. As a disabled writer with energy limiting illnesses, living – as it so often feels – at the outer reaches of the literary universe, sometimes taking a photograph of one of my books within the landscape that’s in them has felt like the only thing I can do for them.

Photographing books in the landscape does come with its own particular perils. My EDS clumsiness means I’m highly likely to tip a book over a wall when trying to get it to stand upright on it, then use up all photography energy I had fetching it from wherever it landed. Then there’s the lake district weather to contend with. You can have the perfect shot lined up in still calm sunshine then as you step back to take it a sideways blast of hail knocks the book over into the mud.

I forget sometimes that paperbacks are much more liable to blow over than hardbacks, as in the case of the paperback of Some of Us Just Fall, which blew from its stony perch into the lake when I turned my back last May. Does this secure it as swim lit, I wondered, but no one answered.

What Will learnt pretty quickly from his time balancing books on the gate is that books look most dramatic in the landscape if the lens is somewhat on a level with them, or a bit below – the covers pop more, if you like. This isn’t too hard when you’re using a gate or a wall to pose them on, but requires a bit more contortion if you’re using a crag, or a rock in the lake. Have you really put enough effort in if you’ve not lain on a beach in the snow to get the right angle on a book, for example?

On friday Katie Hale took some classic behind-the-scenes pictures of me taking photos of the paperback of her brilliant second novel The Edge of Solitude and shared them online along with one of the photos. I’ve been meaning to share some behind-the-shot details for one of the lake poses for months, and even recorded some footage of me wading into the lake and positioning a book, though I forgot to post it at the time and can’t find it now. It take a bit of fiddling around the get balance, angle and light right but the key detail I didn’t get at first is being in the lake to take the photo. The fact I was taking them from in the lake is what seems to have surprised people most.

Because of the rain this last week, the level of the lake is higher than usual, and I was a little worried the water would actually lap at Katie’s book when I moved. It’s one thing to drop your own paperback into the lake; something quite different to drop someone else’s.

Normally there’s a choice of rocks all safely high and dry, instead of just one barely above the surface. Luckily, Katie had a can of pop with her which made a good prop, and even the fleet of ducklings that came to have a look at what I was doing did not knock the book down or wet its feet. One day I will remember that the top of that rock is not actually flat from that angle, though.

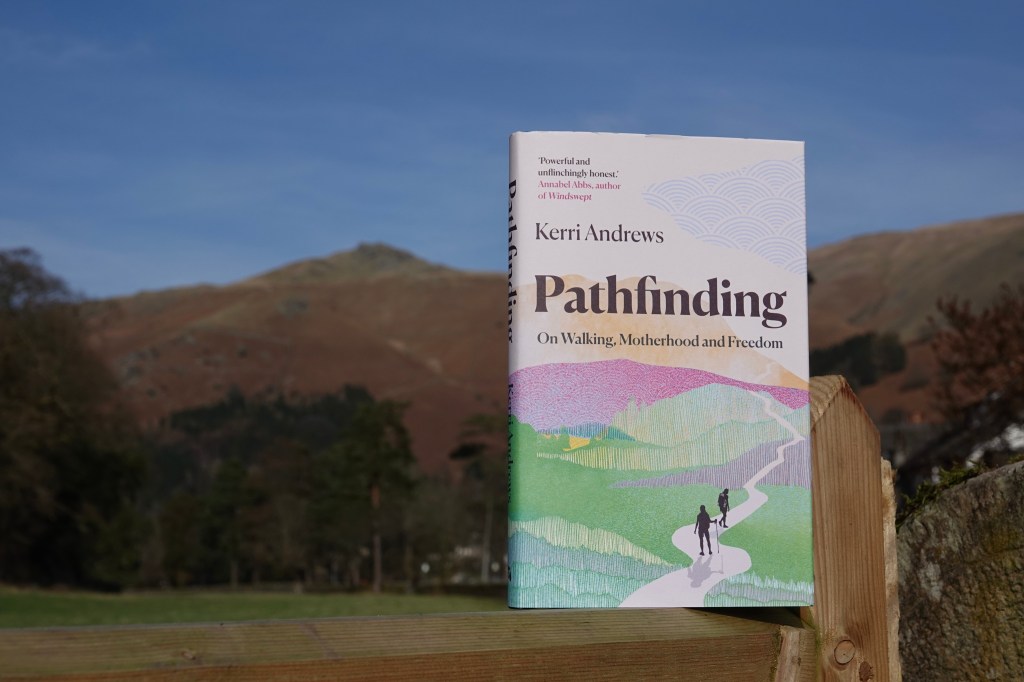

By the time Will and I took over the bookshop in October 2023 the book gate had started to suffer from the continual onslaught of lake district rain, and rotted from its centre, letting lambs wriggle through in the spring and no longer providing a stable surface on which to pose books. Last autumn, it was replaced. Good for the lambs, but less good for the books, as the new gate has a bevelled edge, which we’ve found* is not a safe base for books, though we’ve managed to get a view last shots on it before giving it up. In March I glimpsed out the window to see Will just catching Kerri Andrew’s brilliant new book Pathfinding as it toppled off the gate back into his hands, though he got the good shot first.

We’re experimenting with new places to pose books near the bookshop for best effect and remembering places Will used to use before the gate became his favourite, taking Robert Macfarlane’s new book Is a River Alive? to the river Rothay to gaze at its likeness (I was paddling in the river for this one but it would have been easier and a better angle if I’d got all the way in to be honest!).

As a writer, it’s hard to know if anything you’re doing to try and promote your books is making any difference at all. Publishing can be so casually destroying. You’re promised all this marketing panache when you sell your book to a substantial press, but then there’s a change in editor, or budget, or marketing staff, or head of imprint, or the whole press goes under. Or someone else with a bigger reach publishes a similar book at the same time, and yours becomes an also-ran. Or there’s a world event that makes the subject of your book suddenly awkward or inappropriate or contentious. If you know writers, you’ve heard it all. There are so many ways for things to go impersonally, un-deliberately wrong in ways you cannot account for or control. It happens all the time. If you yourself are a writer maybe it’s happening to you. It’s almost certainly happening right now to a writer whose instagram feed or tour schedule you may have been looking at with envy, thinking how different things would be if your work had the support theirs did. It’s happening to so many of us all the time but it’s maybe useful for everyone to remember it’s hard to see from the outside.

Does sharing an interesting photo of a book make a difference? Probably not much, in the scheme of things. Like any small thing you can do yourself though, it can make you feel less powerless in the process, more active in it. It can give you a sense of a tiny bit more control in the way your work is presented to the world.

As a bookseller, I know a photo can sell a book. It doesn’t happen all the time, but sometimes just sharing a photo of an interesting book online will make someone click on a link and buy it. As a bookseller, and as a writer, I have to believe that counts.

For me, the landscape I live in here in the lakes is so much a part of my writing it only makes sense to include it. It might not at all be the case for others. For me, it’s also, importantly, something I can do, and enjoy doing. It gives me pleasure, and I hope gives some to other people too.

Publishing can be so obscure, and it is so hard to track the impact our work is having. When I was really struggling with not knowing whether Some of Us Just Fall was reaching people out there in the wider world, it was readers’ photographs of the book in their landscapes, their homes, their hands that mattered to me. I love to see photos of my books in other bookshops and in other people’s lives, out there, doing their thing. It gives me hope that my little world is not that little after all, and that my work is travelling even when I can’t. So I try to do the same with books I love too. I bring those books into my world, as the books bring me into theirs. Its a small thing, but a small thing I can do, under the right circumstances of weather and body.

*yes it was me who dropped a book into the field. I am not to be trusted.

2023 eh? That was the year that was.

I’m not going to share my thoughts or reflections on it because they’re all too heavily fogged up by the lens of the present moment and as I write this, huddled up with a hotwater bottle, watching the rain fall for the 6th day in a row, I am going into this transition of years in several flavours of maudlin, so I’ll keep it brief, with a list of things I celebrate from my 2023, and things I am hopeful for for 2024.

The two bigs things of 2023 in my life are these –

SOUJF (soo-jiff-er, to rhyme with Calcifer, for those of us who are too tired to say five words when one will do) will be 6 months old on January 6th, and I hope will keep gaining readers as they trundle along.

I am so grateful to all SOUJF’s readers, everyone who has shared and talked about the book, or supported it in any way. You make it all worthwhile.

This is my first mainstream publication, and I have lots of reflections on this especially, but it’s not the time or place for them.

What I will say is that it’s been more helpful than I had anticipated to remember the poetry mantra that kept me going through all the years of rejections and nonpublications: it’s the work that matters, focus on the work. I’m also inordinately thankful for my wonderful agent Caro Clarke, and to be doing this at a point in my life when I have other writers to talk to about what is normal and not normal, what is personal and not personal about the industry.

The US edition is coming out with Unnamed on March 19th 2024, which is really exciting, and I’m especially thankful for all the thought and care Allison and the team at Unnamed have put into it pre-publication. It’s a different look, and I loved seeing how Jaya Nicely, the art director at Unnamed, thought through the cover. I can’t wait to see the two editions hanging out together.

Thanks to every bookshop and library who has had SOUJF on their shelves, everyone who has made events and talks possible, and again, all my readers.

2. We bought a bookshop!

(the business, to be specific, not the premises, which we’re renting off the previous owner)

My partner Will has been a bookseller all of his adult life, and has been working at Sam Read’s in Grasmere for over a decade. On October 23rd, after a long year of negotiations that felt a lot like something out of a nineteenth century novel, we became Sam Read’s new owners – the seventh generation to take the helm.

We’ve massively grateful for everyone’s support, advice and custom both through the sale process and as we move forward into our first year steering this old and venerable ship!

There have been a lot of work-related frustrations in all areas but as the year closes I want to focus on the good things.

I’ve had work in three anthologies I’m really delighted with in different ways.

1. Three poems included in the National Trust book of Nature Poems (edited by Deborah Alma), with beautiful illustrations.

2. My poem ‘Unwalking’ from Much With Body from the 2019 collaboration with Josie Giles and Anthony Capildeo included in Kerri Andrew’s anthology of women’s writing on walking, Way Makers

3. A new essay about rain and chronic illness in the brilliant Moving Mountains anthology, edited by Louise Kenward.

There are lots more things that are still works in progress, that haven’t quite happened as they were intended to, that have been delayed or disrupted, as you might expect. I’m also sorry to everyone I owe an email to who I’ve failed to email.

Going into 2024 I’m hoping to remember to focus on the things I can control, and let go of what I can’t. To not let what I can’t overwhelm me and distract me from what I can do, and need to do.

I’m working on a little book project which I’ll be able to share more about in the next few months once the manuscript is handed in at the end of January.

I also have most of a third poetry collection together, although the schedule suggests it might not see paper for another couple of years. I’d really love all the problems it addresses to be so obsolete by then that it’s a piece of lyric archeology and I have to bury it and start again but somehow I doubt it. Either way, in 2024 I will try and get more of the poems I’ve written so far out into the world before they turn to dust.

On New Year’s Eve last year we joined Cathy Rentzenbrink’s zoom workshop and out of it I wrote this poem I’ll leave you with. Wishing you all all the best for 2024.

Resolving

To turn my face to the sun at every opportunity.

To wash in its gold like the cat does. To choose

light over productivity. Comfort

over productivity. To be kindly with myself.

To break into simpler parts. To loosen.

The moth-holed clouds of the old year blown open

to let the moon shine through. To vanquish

abstemiousness. Against deprivation.

I will weather these months as the deer do, eating

and resting when I will. Putting all of my store

into personal growth, turning the winter

into velvet and bone, and my own survival.

I will practice my big antler energy. Towards

resting red deer face, the furrow in my brow

less of a comment than a natural phenomenon

and when I am threatened I will leap free and vanish

and when I am threatened I will leap free and vanish

and the space I abandon will be less-than without me.

I am filling my pockets with all the sun I can carry

and turning them out in the burrow of the house

at twilight. I am being lavish with my logs

even before dark, if the day is too dark

though there’s so much winter to burn through.

I am taking it one fire at a time

against the daily emergency of this endless

heedless season of gloom. I am cleaning

my bones. I am lighting all my candles.

I have given up giving up.

Last Friday afternoon, November 10th, Kendal Mountain Festival sent round an email newsletter that included the following announcement:

*For those who’ve accessed the Kendal Mountain Player before, you’ll notice we’re doing things a little differently this year. We’ve chosen to adapt our approach by not recording live Festival events, a move that enriches our focus on delivering an exceptional film programme directly to you.

This statement makes removal of an access provision – the decision at the last minute not to film live events at the festival and make them available to watch later – sound like a positive thing – something that will ‘enrich’ the film programme.

The statement clearly says that Kendal Mountain Festival thinks not offering access to live events is a) enriching and b) adapting. To not film live events means anyone who cannot attend an event in-person is excluded from accessing it, including all the people who had been planning to access events that way this very week. The thoughtless, callous wording effectively says to readers of the newsletter that exclusion is enriching.

Its presentation under an asterisk, as an overthought, means it reads “oh by the way, we’re removing access, and we think it’s a great thing!”. Access is an afterthought, it says, and so is removing it. Maybe readers won’t care or notice? Reader, I noticed. Reader, I care.

The announcement was both a shock and a terrible blow to me, especially as it came less than week before the festival would start. To find out through a newsletter that the festival would no longer be accessible to me or to people like me who cannot attend all or any events in-person, only a few days beforehand, is not acceptable.

Inclusion and access are always a work in progress – nothing can ever be 100% accessible because access needs vary so much – but it is important to be honest and open about what can be offered and why.

On Monday, after waiting all weekend for an official response to a complaint about the wording in the newsletter, I received a long email from the festival director listing all the reasons they are choosing not to film live events, and everything they think they are doing to be inclusive as a festival. It was a familiar format to anyone who has pointed out a problem to anyone ever – a justification not an apology. It focused on things I already know as someone who has been connected with the festival for some years (small team; financial pressures) and presented them as excuses.

It claimed willingness to learn whilst not acknowledging the damage done by the email nor any plan to counteract that damage. There is no accountability.

I’m due to speak at the Festival on Saturday 18th, both interviewing Marchelle Farrell in the morning, and being interviewed about my own book about disability, nature and belonging in the afternoon. It will be a long day for me, which will have a toll on my health, a cost I was willing to pay in return for a tiny bit of hoped for joy, for myself and others. I was looking forward to watching the Friday and Sunday events at home, to prepare and recover. I am also committed to making sure other people who cannot attend events in-person can still access the events I take part in, so this announcement not only affected me as an audience member, but as presenter.

I asked on Monday that a public statement be put out to counteract the damage of the wording in the email. Nothing has yet happened and I have had no further response from the festival director. So this is my statement. This is an edited version of my reply to the festival director on Monday.

What the newsletter said to me is that people who cannot attend in-person – whether because of access needs, covid safety, travel costs and disruption, caring responsibilities, geography or environmental concerns – are not welcome at the festival. Removing access is bad enough, but the particular wording said that their presence is the opposite of enriching, suggesting the festival see us as a burden distracting from its core focus and core audience.

It says to me that I am not welcome at the festival, and that my way of participating does not count to the festival. The impact that this has – physically and mentally – is huge. I cannot continue to support a festival which treats me – and others like me – in this way.

I consider the removal of access to live events to be the opposite of enriching and the reversal of adaptation, and that it is particularly ironic considering the festival theme this year of ‘joy’. If your joy is only possible because some people are excluded from the opportunity to experience joy, what does that say about you, and about joy? About who is given access to joy? About whose joy is prioritised? Joy for one group cannot be built on the despair of others.

In the programme for the book festival there is an introduction from festival patron Robert Macfarlane, in which he writes:

Joy is also born of companionship and community – and here at Kendal, where stories are told by many voices and to many ears, community is at the festival’s heart. Joy can also be the fuel of change.

Robert Macfarlane, ‘A Word From Our Patron’, Kendal Mountain Book Festival 2023 Programme

The newsletter put out by the parent festival on Friday makes a bad joke out of this heartfelt, hopeful declaration.

Macfarlane quotes from the award-winning film We Are Nature, in which Cherelle Harding says ‘joy is my resistance’. This phrasing echoes that used by disabled activists. As Keah Brown writes:

We live in a society that assumes joy is impossible for disabled people, associating disability only with sadness and shame. So my joy […] is revolutionary in a body like mine.

Keah Brown ‘Nurturing Black Disabled Joy’, Disability Visibility: first person stories from the twenty-first century, ed. by Alice Wong

In 2018 disability advocate Andrew Farkash coined the hashtag #DisabledJoy to reclaim joy for disabled people. Disabled joy is resistance against a world that will not adapt to our needs and excludes us at every turn, making the newsletter announcement from the festival all the more painful and ironic.

On a personal level, Friday’s newsletter has taken away not just my joy around this year’s festival, but my joy around everything we have done to improve access over the last four years.

Some people reading this will know a bit about my connection with Kendal Mountain Book Festival (KMBF), a sub-festival within the larger outdoor festival. I first spoke on stage at KMBF in 2017, as a participant in an event for the Vertebrate anthology Waymaking and as a host for an event for This Place I Know. After the 2018 festival, Cumbrian writer Kate Davis approached the book festival with a call to make it more inclusive and accessible, and particularly to include disabled voices and perspectives, and so Open Mountain was created. Paul Scully of KMBF has been a ceaseless accomplice in improving access – always willing to listen and learn, always asking for improvements and adaptations from the festival as a whole. Open Mountain was always a work in progress and ran on a shoestring – the last two years we’ve not been able to run at all because of a lack of funding. The diverse array of speakers at the book festival in 2022 made this feel not too great a loss, in the scheme of things. But the language of the newsletter on Friday left me feeling that the parent festival has learnt nothing from Open Mountain, has not paid attention, has not engaged at all. It actively dismantles the work of Open Mountain, and tramples everything it stood for. It denigrates all the work put into improving access at the festival, which we did because we know it matters, and makes a difference to people. Nature and the outdoors should be for everyone, not just a select few. Now more than ever that should be clear.

I understand the financial constraints around filming of events but the festival has had a whole year to prepare for this festival in which to find alternatives. There are many simple improvements that could have been made to the previous offering that would have improved audience experiences and feedback. There are dozens of different ways to offer remote access to live events without a large-scale glossy filming programme as the festival has had the past few years.

1 in 5 people in the UK are disabled. Pre-pandemic statistics held that 33% of the population live with at least one long term health condition. This number is ever-growing. 1 in 6 of the UK adult population are deaf or hard of hearing. Many of us love the outdoors too! If the festival consulted with groups that focus on access to events and the arts the festival could find much better sustainable solutions to continuing to improve access for all groups. But the festival needs to prioritise access, communicate access, and think it is important to put the work in.

The newsletter signalled to participants who attended past festivals remotely and online audiences excited for this year’s festival that their presence is not important to the festival, that they do not belong there, that it is not for them. It told me that it is not for me.

It’s clear that the newsletter was attempting to put a positive spin on a financial constraint, but the lack of honesty and transparency has had a terrible effect.

I have mulled this over since Friday, but I will be attending the festival as planned on Saturday, for two reasons:

* I believe in keeping my commitments unless it is physically impossible to do so

* On balance I think my visible presence at the festival talking about access, exclusion, and disabled joy will do more than my absence would.

I have had it confirmed that events at the book festival will be audio recorded and shared, along with transcripts, after the festival, at no cost.

I have asked for a retraction of the newsletter, and a public apology for both the announcement in the newsletter and its particular wording, to make it clear that the festival does not believe it to be enriching to exclude people from the festival, and that it is working to improve access in the future. This needs to be supported with actions – arranging training on disability inclusion and anti-ableism for the whole festival team and engaging an access consultant for future festivals, as well as prioritising access in funding applications.

Yet again, this has drained me of all joy over the festival, and also drained me of precious energy I should have been spending on my own work.

I will not waste any more of my very limited energy hitting my head against the brick wall of the festival expecting it to transform into an open door. Unless the festival shows a commitment to real change, the kind of change that admits joy for everyone, and not just the few, I cannot work with them again. This brings me great sadness, and this is what I will be talking about on Saturday: the exclusion of joy, the exclusion of community, the denial of companionship, the erasure of many voices.

Update: As of November 24th, two weeks after the newsletter, I’ve still had no response from festival CEO Jacqui Scott after my email of Monday 13th.

Further Update: the year ends and still no response from festival CEO Jacqui Scott other than to post lots on social media about how inclusive and joyful the festival was. This is not the way.

In my latest poetry collection, there’s a poem made out of lines from other people’s poems – a form called a cento, which has a history going back thousands of years. The word ‘cento’ once referred to planting trees, but came to mean patchwork clothing, and then a poetic form made from fragments of other texts sewn or planted together. The cento in Much With Body is called ‘When all this is over is over’ and is made from lines from poems which include the phrase ‘when all this is over’ or ‘when this is over’ (obviously not a complete list). It is an early pandemic poem – a Plague Year Season One poem – responding to both people’s hopeful attachment to Kathleen Jamie’s beautiful poem Lochan that Spring, with its wistful projection ‘when all this over […] probably in June’ and to Boris Johnson’s claim in March 2020 that we could ‘send coronavirus packing’ within 12 weeks.

My knowledge of pandemics is that of a voracious reader and consumer of culture, not of an epidemiologist, but even so to me the idea that we could be seeing an end to the pandemic within such a short time was nakedly unrealistic. The poem knows by the time it really is all over, so much would be broken, lost, reformed. ‘There will be no god when this is over’, the cento repeats, borrowing from Ruth Awad’s amazing poem, ‘The One where I beg’.

Now, in Plague Year Season Three, this poem has an increasingly ironic tone for me, when so many in the literary world are acting as though it is all over, has been over, continues to be all over.

There are fewer and fewer ways to track case numbers in the UK, but we still do have some statistics on deaths, and they are not good. Between April 19th and 22nd there were 1920 covid deaths recorded in the UK. Deaths represent the very tip of the iceberg of the damage covid is doing. By now it is clear how many people have ongoing debilitating effects from even ‘mild’ covid infections months and years afterwards, and recent studies have proved covid causes organ damage, including causing brain abnormalities, and a 72% increased risk of heart failure. The effects of mass infection will be being felt for generations to come. Those of us who know we cannot afford to risk these consequences are frequently made to feel foolish and selfish, for many of us repeating and reinforcing decades of medical gaslighting.

Yet here we are, in April 2022, knowing all this, with maskless indoor in-person events once more standard, and remote options falling away week by week.

I’ve been asking for people to consider retaining remote access for events – first gently; increasingly desperately and pleadingly – for two years now. I am so exhausted by asking. I am far from alone. Around the world I see the same anguished reports from those of us unable to ignore the continued presence of the pandemic, increasingly shut out of cultural activity.

As Vic Wreford-Sinnot wrote last month: ‘the way the arts sector is behaving when the pandemic is still raging is just not normal. The arts are facing some of the biggest moral dilemmas in living history.’

Vic Wreford-Sinnot, ‘Crucial Conversations With Disabled People: Just What is the New Normal?’

Many disabled people found that access to the arts and education opened up for them when nondisabled people needed it. For those who couldn’t attend events in-person before the pandemic, it was bittersweet to suddenly be told access was possible where it had previously been refused.

Many predicted how access would be denied again as soon as nondisabled people no longer demanded it.

This month, London Book Fair justified its decision to run in-person, without mask enforcement, ventilation, or checking of vaccination status or negative tests, after attendees from around the world were infected at it, on the basis that the gathering is ‘key to the publishing industry’.

There are days when I feel there can be no place for disabled creatives in an art world so attached to presenteeism that it will risk the bodies and minds of those who constitute it. What I get back a lot from event organisers is that it’s too hard and/or too expensive to offer remote access. This doesn’t have to be the case.

I’m gathering some of the basic advice I and others have given about remote access here, so I don’t have to keep typing it out, and so it is easy to find in one place.

This is an imperfect gathering of some of my thoughts and some observations of what has been successful for others, and I hope to keep adding to it. If you have any advice or changes to suggest, please get in touch.

1. Accessibility for audiences and performers should be considered at the earliest planning stages for every event, not tacked on as an afterthought. If you build accessibility into your planning and funding applications it will be better for everyone.

2. Online & In-Person strands must be treated as equal variations – with benefits for different people’s needs. Don’t describe in-person events as live/real and online events as not real/not live. This reinforces a hierarchy that suggests all online events are substandard substitutes. (I know some of you feel this way but have a heart, I beg thee!)

3. Offer hybrid options as standard for everyone – not just for people you know are disabled or people who make access requests. Remote options give amazing access to people who can’t shift their lives around to go to a town to watch events in-person for 5 days, for eg., but can watch events online whilst making dinner. Don’t make us beg!

4. No one should be made to feel like they have to do in-person or lose work.

5. No one should be forced to disclose medical conditions.

4. There are lots of different ways to make events or whole festivals hybrid. We need to be creative and thoughtful with how we do that.

5. If you’re running hybrid events advertise both strands equally! They are both brilliant for different audiences. You will reach many more people online if you make it obvious how you access your events online and easy to book online tickets.

6. If you are running an in-person event strand, make sure that your in-person events are still as accessible as possible to as many people as possible too. As well as all the normal aspects of making a physical space accessible, this also means putting in place as many protections against covid infection as you can, such as making sure you have good ventilation, and requiring masks unless people are exempt. This makes it safer for everyone.

7. We can’t meet the needs of 100% of the people all the time, but we can do our best, and that means a lot. Trying is better than giving up.

8. Be clear about what the event will involve and make sure everyone involved understands what will happens eg. if it is going online, how long for; how will recordings be used in the future.

9. Don’t forget your online speakers if most of you are in-person! Make sure festival instructions are not just geared towards in-person attendees, and if you usually give an in-person speaker access to other events at a festival with complimentary tickets, make sure you do the same for online speakers for events that are accessible online (even if that’s after the festival itself).

10. Show solidarity!

If you’re nondisabled and are invited to work at or attend an in-person event ask questions: will there be remote access options for performers and audiences? will there be masks and ventilation in-person?

If you’re involved in running events think: how can I make sure people who can’t attend in-person aren’t excluded from this event? how can I help create a more equitable future?

One of the most simple things people can do to show solidarity is to normalise mask-wearing. In an indoor place with other people breathing? wear a mask. It will protect you and others, and make it easier for other people to do it without them being singled out.

Remote access is enabling audiences and/or speakers to attend an event without having to be in a room together.

Remote Access existed long before the pandemic in many forms, from telephone interviews on the radio to videochats, including:

1. Online Events

When everyone needed remote access online events became common, and people got used to speaking and attending events which were online only, on platforms which enable audiences and speakers to interact to different extents including but not limited to:

Some of these platforms enable you to record the event and share it afterwards too, so you can add it to an archive of events on your own website, or through a video hosting platform such as youtube or vimeo.

Provide closed captions on all online events. These can be edited afterwards for accuracy if you’re uploading it after the event has ended.

To include signing speakers or attendees, make sure you have Sign Language interpreters.

2. Filmed Events

A filmed event can be shared in real time as an event happens, through a live-streaming platform, or afterwards, on a website or through eg. a youtube or vimeo channel.

There are lots of ways to film an event, from using a smart phone on a tripod, to hiring a film crew, depending on your budget and the size of the event.

Provide close captions on filmed events. These can be edited afterwards for accuracy if you’re uploading it after the event has ended.

To include signing speakers or attendees, make sure you have Sign Language interpreters.

3. Audio Recording of Events

Many literary festivals and event series audio-record events to create an archive that can be shared online (for eg. through soundcloud) or podcasted. This is a form of remote access that can be pretty simple to do.

If sharing audio-only provide a transcript.

4. In-Person events where one or more speakers appear virtually on-screen from a different location.

This was one of the most common forms of remote access for speakers pre-pandemic, and as previous festival director Eleanor Livingstone recently noted, was something StAnza Poetry Festival had been doing since 2009, when a poet’s travel plans failed. Many festivals and conferences have done this to include international writers, or very busy writers who don’t have time to travel! This has also become a common feature of hybrid events.

The word ‘hybrid’ has generally been applied during the pandemic to events which are both in-person and online.

Lots of small events organisers and festivals are complaining (understandably) of the cost of bringing production companies in, but others have found more lo-fi ways to do this and were doing it long before the pandemic. Hybrid doesn’t have to mean expensive with high production values. Jamie Hale, with the support of Spread the Word, has made an excellent guide to making events hybrid without it costing lots or being really complicated, which you can find here, and in the resource list below. Of course, training up your own people to do the tech is the most sustainable option for a hybrid future.

Often people think making an event hybrid means having to live-stream an event whilst it is happening, which can seem daunting to some event organisers, and does require more technical know-how and a decent internet connection. Live-streaming doesn’t have to be complicated, but there are other options to provide remote access too.

Some festivals describe themselves as hybrid when some of their events have remote access, but not all of them, which can be confusing as an audience member trying to work out what you can or cannot access.

Often this means only events seen as big sellers get live-streamed, so some of the more unusual content is not made accessible. Whilst this seems on the surface to make financial sense (you think you’d get a bigger online audience for a famous writer than a lesser known writer with a small following) it doesn’t make sense if that famous writer has lots of other content available online.

We’re a creative industry, we should be able to be creative about how we make this happen, to make sure everyone gets a good experience. A good experience doesn’t have to be a glossy experience: often what we are seeking is simply to be part of the conversation.

This might mean not, for example, trying to run a single workshop which is simultaneously online and in-person, so the workshop leader has to go back and forth between remote attendees and people in the room with them, but instead offering two different versions of the same workshop: one in-person, and one online.

Some things to consider when planning a hybrid event might be:

Being Hybrid: A cheap and easy guide to hybrid events by Jamie Hale and Spread The Word.

Red Door Press Keep Festivals Hybrid guide to putting events online. This has lots of handy tech info including details of what equipment you might need for live-streaming.

The Inklusion Guide. Coming soon, this will be an easy-to-use guide to best-practice accessibility across hybrid, online and in-person events.

Guides to working with disabled writers & audiences from the Society of Authors ADCI group.

The Society of Authors statement on retaining event access.

Recorded zoom session on making events accessible from author Amanda Leduc through the Festival of Literary Diversity, in Canada.

Brella blog on benefits of hybrid events.